New marine specimens were collected along the shore of Dinard, a town in Brittany on the « Côte d’Émeraude », during the first sampling mission that was executed entirely by the ATLASea program.

Beach of the « Pointe de la Roche Pelée » and Marine Station of the Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Dinard. © ATLASea

From June 24 to July 6, the marine station of the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle in Dinard buzzed with scientific activity. More than 60 participants, including 15 taxonomists and three photographers, took part in the inaugural sampling expedition carried out entirely by the ATLASea program.

Welcomed and assisted by some twenty staff working at the station, the teams achieved remarkable results at a very steady pace. A total of 472 marine species were collected and sent to Genoscope in Évry for genome sequencing.

A few months before, some ATLASea team members had completed pilot sampling missions in the Mediterranean and New Caledonia, which allowed them to fine-tune the logistics chain (sample collection, identification, and conditioning). They were now ready to use their protocols on a greater variety of animals.

The harvest

Two semi-rigid boats, the Bleiz-Mor and Émeraude Explore, were used to escort divers for deep-water visual harvesting off the coast of the Côte d’Émeraude and in the nearby harbors.

Left, Michel Le Gall on a semi-rigid boat. On the right, Line Le Gall, director of the DIVE-Sea targeted project, equipped with a rebreather, a diving device that offers greater autonomy of use. © ATLASea

The Louis Fage, a trawler from the marine station, regularly passed through the sediment-rich area just outside Saint-Malo harbor. The staff on board collected mud, algae, shells, and fine sand, where tiny specimens reside, using nets, a dredge, and a sediment bucket.

“In specific types of sediment, which are very heterogeneous, with lots of crevices, we can find around a hundred species in a sample of less than a square meter. It’s an enormous biodiversity“ according to Sébastien Aubin, research officer at the Dinard marine station.

After returning to the station, the sediments had to be separated by size and sieved in order to extract the specimens from their substrate. The last stage was to catch them, which required dexterity and sensitive handling because some , like amphipods, were quick swimmers.

Sorting bench at the MNHN marine station in Dinard. © ATLASea

At the same time, some participants went to the seaside to gather different kinds of specimens, particularly fish. The ATLASea program had not previously included these vertebrates into its collecting plan, therefore this was a first.

On the left, Marie Sémon, professor at ENS Lyon, visits the Dame de Jouanne site at Saint-Briac-sur-Mer, and on the right Cécile Bernard, research director at MNHN, and two trainees, Charli Rossi-Burden and Flora Roest Crollius. © ATLASea

Alexandre Carpentier, senior lecturer specializing in the functional ecology of fish-habitat relationships on the land-sea continuum at Saint-Enogat beach in Dinard. © ATLASea

Identification

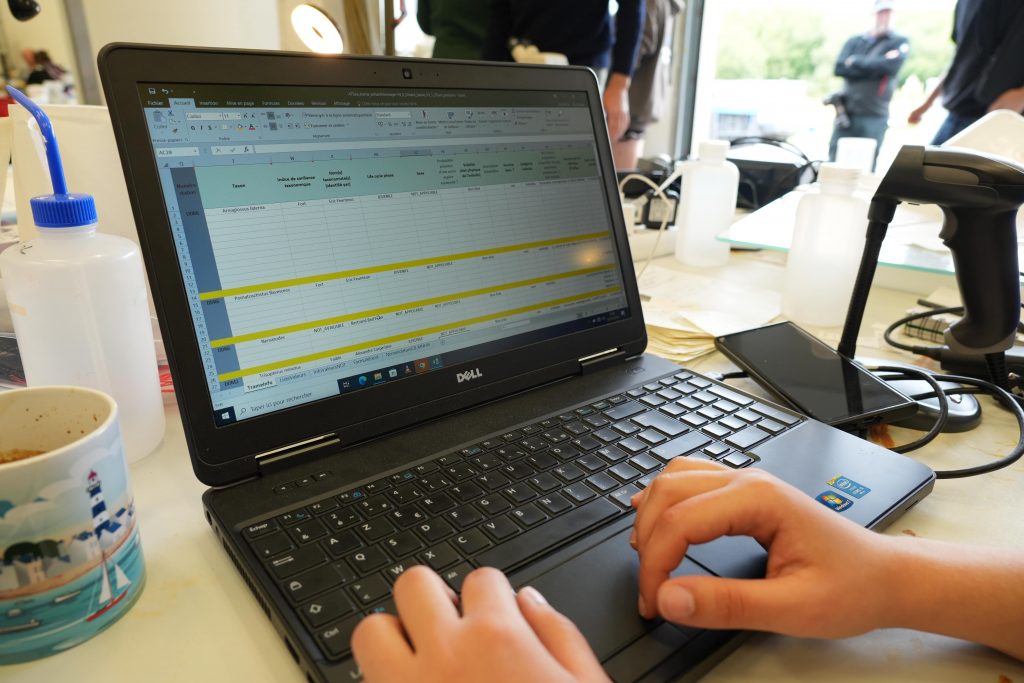

During the specimen identification phase, the proximity between the taxonomists and the biologists of Genoscope made species recognition much easier. They were able to quickly identify the sex and anatomy of the specimens, and determine which body tissues had the highest concentration of DNA.

In addition, workshops led by taxonomists were organized for the first time. Participants learned how to identify ascidians, algae, annelids, crustaceans, molluscs, sponges and bryozoans, fish and elasmobranchs, as well as benthic biocenoses and habitats.

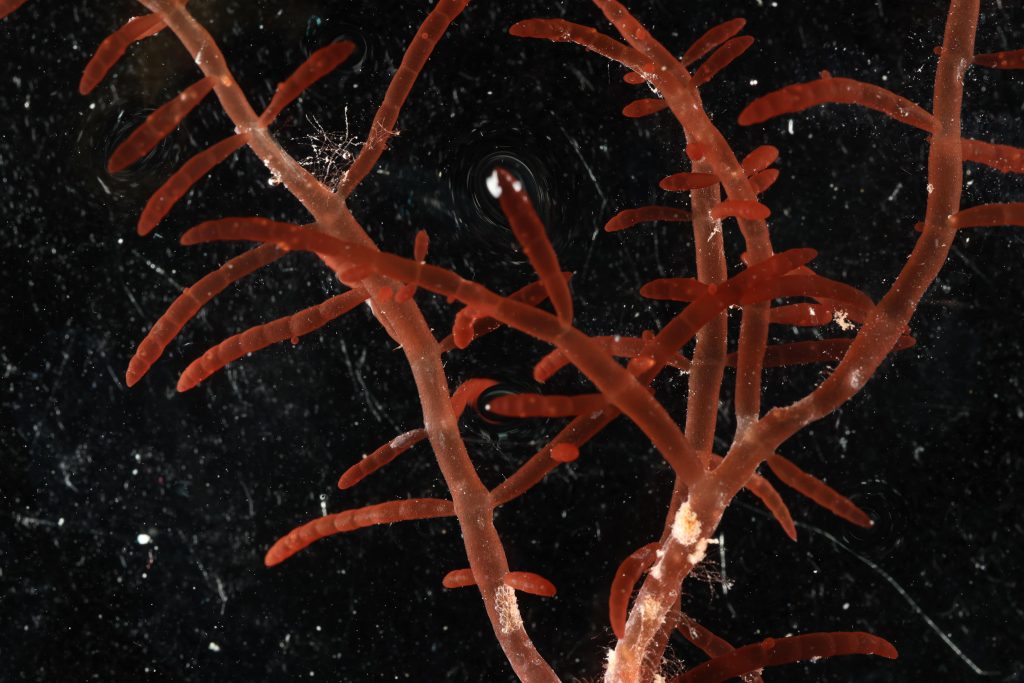

On the left, Riccardo Virgili, engineer at the University of Naples. On the right, an annelid under the microscope. © ATLASea

Conditioning

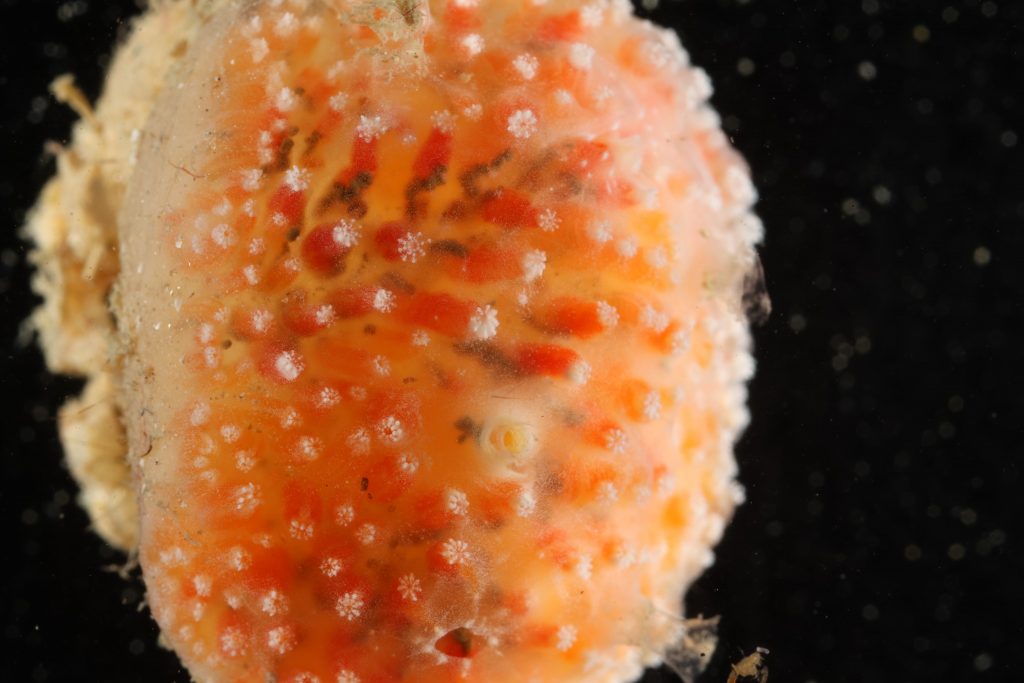

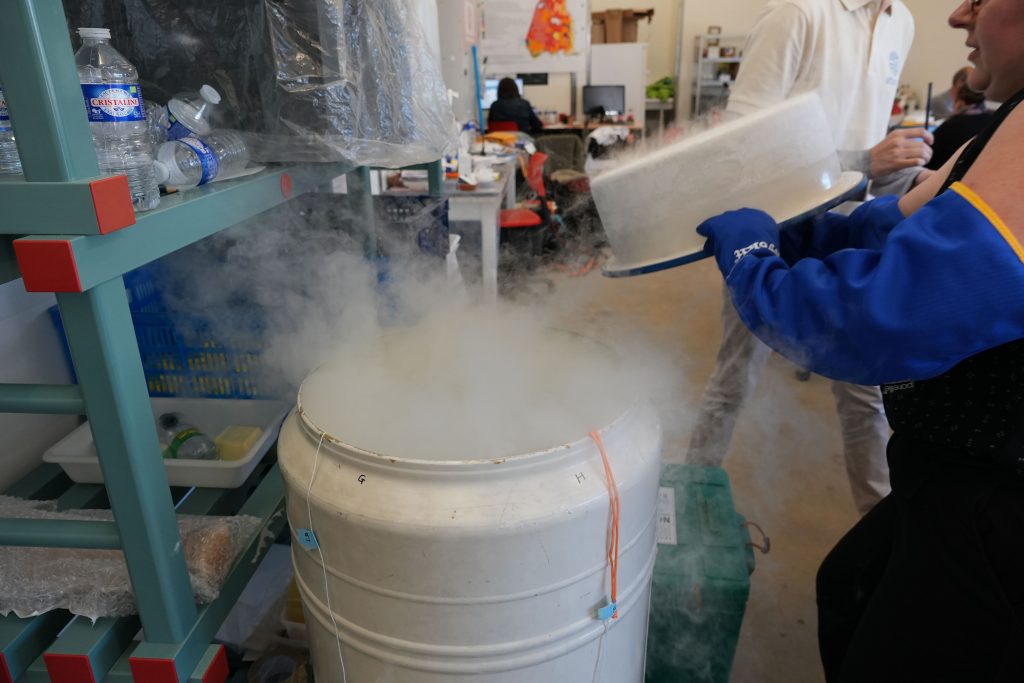

After checking that the identified specimen was not in existing databases, and having carefully photographed them using high-performance new equipment, Genoscope biologists had to work fast: select, clean and tube the best samples before plunging them into liquid nitrogen for instant freezing.

While waiting to be sent to Genoscope, the small sample tubes, marked with an identification barcode, were stored in a freezer at -80°C. For each species, there was a minimum of 3 sample cryotubes, and 10 if there were enough samples.

Left: labelling of sample tubes. In the middle, the species characteristics are entered into the frame, the database containing all the species to be sequenced. Right, opening a liquid nitrogen tank. ©ATLASea

Challenges

One of the many challenges that biologists may soon encounter is sequencing materials weighing less than 100 mg. Indeed, enough tissue with a high concentration of DNA is necessary to sequence a specimen accurately, and current protocols need at least this amount of tissue.

Another challenge will be to extract DNA from algaes. Indeed, in the environment where they live, i.e. at shallow depths to have access to light and close to the coast to settle on a rocky substrate, the swell, is often very strong. To absorb this energy, algae need to be flexible, so they have developed a wide range of polysaccharides – a class of complex carbohydrates – in their cell walls, giving them flexibility and a slippery, viscous appearance. According to Line Le Gall, director of the DIVE-Sea targeted project and an algae specialist , “these polysaccharides are very similar to DNA and are often co-extracted with it”, which greatly complicates post-extraction processing.

Other species will also be difficult to sequence. In the meantime, here is a selection collected during this mission.